|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

BLOG

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

Mikalogue: The Fighties

Kit: Oh hi, baby, I didn't see you there. How are you today?

(Pause.)

Mika: Yaaaaa!

Kit: Oi! What are you - stop biting my arm!

Mika: Kitty ambush! Bite your arm and defeat it!

Kit: Mika, stop that at once!

Mika: You will submit to Genghis Cat!

Kit: Mika, what on earth is wrong with you? Get off!

Mika: Aha, fine foe, think you push Genghis Cat away? Return and subdue your arm!

Kit: Mika, I wasn't bothering you. I was just sitting here and you rush up and grab me, you bad girl.

Mika: Yaaaaaaaa!

Kit: That's enough. Stop that at once.

Mika: Aha, tail, don't think Mika the mighty doesn't see you lookin! Face your doom!

Kit: Calm down!

Mika: Cushion attack! Yaaa!

Kit: You've just got the fighties, haven't you?

Mika: Chaaaarge!

Kit: I don't know what's got into you lately. Are you having a cat adolescence?

Mika: Fight! Fight!

Kit: No, I'm not going to play with you if you're going to be like that.

Mika: Victory!

Friday, January 23, 2009

I'm freee!

First, to answer the question of the previous thread, I brought in two books - an Alexander McCall Smith and Sarah Waters's Night Watch, which is the only one of hers I haven't read yet. In the end, though, I didn't read them, as the waiting times weren't that long, I was too nervous to concentrate, and I spent the time talking to my fiance instead. There was no TV blasting in the ward, mercifully; the surgery had some cheery music on in the background, but that was the point where they anaesthetised me so I can't quite remember what. I'm feeling a bit fragile and I'm not allowed to drive, drink or operate heavy machinery today (three things I don't do anyway), but basically I'm all right.

What did I learn from the experience? Mostly, that I have a really, really big thing about independence.

Also, that I'm more scared of medical procedures than you'd expect an educated person to be.

The latter is easy to account for: my father is a lawyer who specialises in medical negligence cases. The work stories I grew up with involved doctors who had messed up but good, causing terrible and permanent injuries. The surgery I was in for involved removing a benign lump from the region of my back under light general anaesthetic, and I'd never had more than a local before. My rational mind knew that this was a minor procedure, but certain phrases wouldn't go away: anaesthesia awareness, spinal paralysis, death under anaesthestic. A kind student came by and asked me how I was, and when I mentioned I was scared she took note: I was supposed to have a three-hour wait, but when my fiance went to see if that was definite, she apparently told the staff that there were a couple of cancellations and that I'd be a good person to move up the queue because I was anxious, and the next thing I knew people were walking into my little bay telling me to hop on the bed. Nice of her, really.

Which was where the independence issues kicked in.

I'd considered myself all right up till then; frightened, but coping. Once I was lying on a bed and getting wheeled along the corridor, I was overwhelmed with a sense of helplessness. Ceilings rushed past, doors were opened for me, I was trollied along with no control at all. They got me into the surgery, where there seemed to be about a dozen people milling about, and one of them got hold of each of my arms. The nice anaesthetist was knocking my wrist to put a drip in it, which was dealable, but there was a nurse taking my blood pressure on the other side, which made me panic: one mildly painful procedure I could deal with, but two at a time was too many. It split my concentration, and I wasn't sure I could maintain control of myself. Someone was sticking ECG badges to my chest, my arms were no longer my own: I felt surrounded, outnumbered. Once you're in surgery people start working on you like mechanics on a car, and while it's an efficient way of doing things and efficiency matters a lot in a public health service, if you have control issues, it's freaky.

Well, something went into the drip; the anaesthetist told me it was a pre-anaesthetic, and the stuff on the ceiling got a bit swimmy. The next thing I remember, I was surrounded once more, this time by two nurses talking about some other patient and messing with my arms again. This wasn't where I'd expected to wake up: I'd seen people wheeled back into the ward asleep, so I'd anticipated being back there, which would have been okay - I could come to peacefully, my fiance would be there, and he was on my side. Instead, I was somewhere strange and nobody seemed to be talking to me, and I got panicky again. Coming round wasn't what I'd expected to begin with: I'd been picturing a consciousness jump, a kind of lights-off, lights-on transition from one place to another; instead, I did know that time had passed. There was just a hole in the middle, and I wasn't sure where its edges were. I asked if I'd be going back to the ward soon, the nurse told me I'd already asked that, and I started to cry.

People come out of general anaesthesia in a variety of ways: they weep and wail, or giggle, or act groggy; my fiance had seen one polite woman being wheeled back in thanking the nurse like a slowed-down but appreciative recording. I was wheeled in crying and insisting that I wanted to go home.

The interesting thing about this is that I remember it - and I was totally convinced I was fit to be discharged. I was crying like a child, my blood pressure was all over the place and I was apparently talking slow and confused, but in my own perception I was fine. I knew exactly what I needed, there was nothing wrong with my judgement, I was crying because people weren't taking me seriously, which was insulting, because I was fine and knew exactly what I was saying. In a sense, I was right - I was saying that I wanted to go home, and I did want to go home - but I was also bitterly resisting the idea of any kind of dependence on the staff, which, considering I'd been unconscious ten minutes ago, was far less reasonable than it seemed at the time.

I wanted to be in complete control of my own fate. Finding that I wasn't, I just cracked and lost any control at all.

So my fiance watched a nervous adult woman being wheeled out, and got back a pathetically regressed mess, who greeted him with a wave and then started sobbing, 'I want to go home, they're talking over my head and I want to go home...' I kept asking the nurse to take the drip out, to let me get dressed, to let me leave, even though I was undoubtedly not ready for any of those things. They offered me a sandwich and I declined, insisting I wasn't hungry, even though I'd had nothing all day except a smoothie about nine hours previously; after about half an hour of recovery time, the nurse pointed out that the headache and dizziness I was complaining of were probably hunger and pressed some fruit squash on me, but up until that point it genuinely hadn't occurred to me that the headache and the fasting might be connected. Accepting food would have been accepting their hospitality, and I didn't want it. The surgery was over, as far as I was concerned, and I wanted out of there.

Why did I freak out? People react unpredictably, according to the staff - I wasn't the only one to be wheeled in weeping - but I do wonder whether people who usually care a lot about self-control and independence tend to collapse the most. (Anyone else's experiences that confirm or contradict this, I'd be interested to hear.) The fact that I was scared probably had a lot to do with it, but the big thing that upset me was that I had no say over what was going on. I got wheeled instead of walking on my own two feet; people were fiddling with my arms and I couldn't stop them; something major had happened to my body and I didn't remember it; I was told I was repeating myself and I didn't remember that either; I didn't wake up where I expected; people were treating what I said (not without reason) as babbling rather than sense. So I wanted to go home - my safe place, of course, but also the place where I was in charge of my own destiny. I got touchy under the anaesthetic; in my confused state, being treated like a patient seemed like in unbearable assault on my dignity.

Which is something I generally pride myself on - and tend to treat as inseparable from self-reliance. There's been more than one occasion in my life where I've delayed asking for help until long after I needed it because it was so important to me to feel that I could manage. The Coper is a role I find hard to let go. In the normal run of things, I say please and thank you, I try to act intelligent, I conceal disappointments, I hesitate to accept help because I want it known that I can handle myself. In a situation where people correctly divined that I couldn't, I just couldn't accept it. Attempting to comfort me, my fiance suggested I relax and trust that the hospital procedures would take their course for the best, and think of myself as being on a boat moving safely downstream to its destination; I tearfully responded, 'What kind of a bullshit metaphor is that?'. As far as I was concerned, I wasn't a passenger, I was a prisoner. I spent a good ten minutes insisting that I was fine and ready to leave before I wore myself out and gave in to a short nap out of sheer exhaustion; after that, I started being politer to people for no other reason than that I'd got the vague idea in my head that I was upset with everybody for perfectly legitimate reasons, but because they were mean they'd never believe that and would only let me go if I pretended to accept their authority.

Things moved along, and I was finally discharged about an hour and a half after I came round from surgery, which is fairly fast according to my pamphlet (it predicted one to six hours' recovery time). By the end, I was prepared to tell the nurse that I'd been confused when I came round and I was sorry if I said anything rude, which seemed to please her, patients apologising for rudeness perhaps not being the universal rule. But it took several more hours for the weepiness to finally wear off and for me to be able to accept a basic fact: I was out of my head on drugs, and my judgement was all shot.

The human brain is a rationalising organ, and resists any knowledge of its own fallibility. One of the best examples of this I've ever heard is a story a doctor friend told me. She was working on the wards, and in one bed was a man who had lost his short-term memory. But because he'd lost it, he didn't know he'd lost it: he couldn't remember the doctors telling him. So here he was in a hospital ward, but he didn't feel sick; there be some other reason he was there. And he came up with one: he was there to sell watches. He kept going up and down the ward trying to sell people watches, convinced that this was why he was there. His brain had a gap, and plugged it, as brains tend to do. The plug was made of false conclusions, but he just couldn't tell.

Ask me today if a patient who's just emerged from surgery under general anaesthesia should be discharged five minutes after she comes around, especially if she's crying, and I'll tell you no, of course not; a hospital would be completely irresponsible to let her go. Yesterday, I completely lost track of that. It's an interesting lesson in perspective, in a spooky sort of way: never forget, you might be out of your mind.

I've been considering, too, how these issues I apparently have relate to other areas of my life, including writing. One reason I don't drink, I suspect, is that post-adolescence I'm no longer comfortable with feeling drunk. It involves a chemical suspension of your self-control, and I think I tend to fight the feeling rather than enjoy it, which doesn't lead to a happy experience. But while I was talking about not wanting to lose it, my fiance asked where writing came in - don't you have to let go for that?

Well, sometimes. Some days it's a grind, and serious self-control is the only thing keeping me at my desk. But in other circumstances, it can be like a controlled detonation. I can let go - but on my own, in a safe environment that I'm in charge of.

My fiance worried me a bit by speculating whether anaesthetic strips you down to some kind of core self, which I hope is not the case as it suggests my core self is a confused and frightened five-year-old with no manners, but something else occurs to me. The way I was acting - blurting out 'What kind of a bullshit metaphor is that?', for example (a comment I subsequently apologised for) - is much more the way some of my characters act than the way I usually do. I seemed to have picked up some of their most difficult personality traits: Lola's touchiness, Anne's vulnerability, Henry's stubborn hatred of being handled. Which suggests that a lot of the time, I put my post-anaesthetic emotions into my books - or, more generally, the anaesthetic brought out emotions that I usually only show in my fiction. There's also the general point that I possibly wouldn't have woken up crying if I hadn't gone in afraid, and scaring yourself is the price of imagination, but the main thing, I think, is that I tend to put my less controlled feelings into my fiction, unless I'm on drugs.

So there you have it: general anaesthesia and surgery were not much fun, who knew? But I'm basically okay, if a bit sorry for myself (what? you couldn't tell?), and the experience was educational, so there's always something to learn.

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

Good hospital reads

Now, hospital reads are a special category. You're in an uncomfortable chair or a starched bed, usually in a clean but rather bleak white room, one eye on the clock, torn between wanting to get it over with and really not looking forward to the experience. Circumstances are, to say the least, distracting. The book you bring with you has certain requirements:

1. It needs to be long, unless you're bringing several books, especially if you read as fast as I do. Not only does it have to last out the wait, it helps if it's comfortingly thick, so you know it'll last and don't have to worry about spinning it out.

2. It needs to be properly gripping. When the choice is between reading the book and staring at the wall, you need the kind of story that you wouldn't want to put down even if you did have anything else to do.

3. It needs to be lucid: too intense a style can be demanding when you can't take breaks from it. Last time I was in hospital I brought Frank McCourt's 'Tis; it's an excellent book, but the style is very strong, and after a while, it started to bake my head.

4. For preference, it should be a nice mental space to inhabit. Your environment is already stressful; if your book is full of squalid settings, the whole world starts to taste bad.

5. As a sub-set of this, it's preferable if it's written by an author with a fairly positive attitude towards people. Sad stories are fine, but a book in which everybody hates everybody else and they're all bastards is just a bit much when you're stuck in a ward.

7. The plot needs to be easy to follow without being bland or simplistic. Too many characters to lose track of is bad, but blindingly obvious is just boring.

7. In terms of quality, it needs to be meaty enough to hold your attention, but not so difficult that it makes you tired. A frothy chick fic is fine for half an hour on the bus, Crime and Punishment is fine on your own sofa, but neither suits a hospital. Good but approachable is the key.

8. It needs great character writing. If these imaginary people are your sole distraction from the ward setting, then thin characterisation makes it impossible to care about anything that's happening to them.

9. It needs to be relatively uncontroversial. Not that they'd be on my top pick list anyway, but I'm not about to read The Fountainhead in a hospital funded by socialised medicine, or Gone With The Wind or a Fu Manchu novel in a hospital where doctors and nurses of all races work hard to keep people from dying, or The Story of O for, well, lots of obvious reasons. Hospitals are public and you don't want to feel defensive; neither do you want to offend staff who are doing their best to give you good treatment or fellow-patients who are probably feeling nervous already.

What can people recommend? I'd put on my list George Eliot's Middlemarch, Jane Austen's Emma, Donna Tartt's The Secret History (which is full of beautiful descriptions, a particular benefit), Margaret Atwood's The Robber Bride or Alias Grace, and Sarah Waters's Fingersmith (breaks the 'no squalid places' rule, but she writes so beautifully that the book itself doesn't feel squalid.) But I've read all of those, so that's not much help. Bearing in mind that I don't much go for most fantasy novels, can anyone suggest anything?

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

Yay!

Being that the guy's right of centre by any sane standards, I doubt I'll like everything he does over the next four years. But you know what? I don't care. He appears not to be a lunatic, an incompetent or a bastard, so I'm happy.

Congratulations America.

Monday, January 19, 2009

And we have a winner!

So, the winning ones. Second runner-up goes to Dash, for the elegantly simple 'Splash!'

First runner-up goes to Michael Mock, for some really good sentences which sketch in rather a lot of background.

But the winner of the book is going to have to be Amaryllis, who made me fall about laughing with 'Call me Fishmael' - not only hilarious, but oddly appropriate for the story's theme; it seems to sum it up with the memorable succinctness of an advertising slogan, and I suspect I'll find myself using it when explaining the book in future. So, Amaryllis, if you'll send your e-mail address to kitwhitfield@hotmail.com and let me know where you want it sent, I'll pass on the news to my publicist. It will probably have to wait for the official publication date; I'll try to get hold of it and sign it if you like.

However, you're all winners here, so by way of a shared reward, you get ... (fanfare please) ... a sneak preview! This is the actual first paragraph:

Henry could remember the moment of his birth. Crushing pressure, heat, and then the contact with the sea, terrifyingly cold - but at the same time a release from constriction, the instant freedom of the skin. His mother gathered him up in her arms and swam to the surface, cradling him on her slick breast to lift his head above the water for his first breath. Henry never forgot it, the mouthful of icy air, the waves chopping his skin, a woman's arms holding him up in a world suddenly without warmth.

Wednesday, January 14, 2009

You know what I've got?

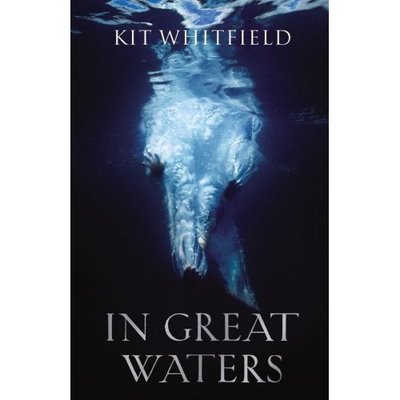

I've got a first copy of my new book!

On Monday I met with my charming publicist, and wouldn't you know, copies of Book Two - entitled In Great Waters - have just come off the press. I'm very excited; it's glossy and handsome, and looks great.

Of course, at this stage I can't bear to read it. After writing it, rewriting it, copy editing it and proof reading it, I've had absolutely enough of its contents for the time being; right now, I'm scared to look inside it in case I spot disastrous sentences and end up wailing 'Why? Why? Why didn't I change that while I still had the chance?' However, this is just the oversensitivity that comes from a) being the author and b) reading it too many times; no doubt I'll like it better when I've had a rest from it. All things considered, I'm pretty pleased with how it's come out.

I'm particularly impressed with the cover image. The subject of the book was a horribly difficult one to find a picture for. I say this with feeling; I've compiled illustrated books in my time, and when it comes to matching words and pictures, reality tends to be stubborn: the right poem or the right photograph very often only exists in your mind, and artists throughout history, the pigs, have failed to provide you with what you need. This book in particular involved two completely different subjects, underwater life and court politics, and if you can think of an image that suits both of those, you're a cleverer person than I am.

Fortunately for us, Lily Richards, the picture researcher at Random House, is a cleverer person than I am. The image she tracked down is by the fine arts photographer Narelle Autio, and its underwater beauty combined with a suggestion of violence and struggle, as well as an air of thrown-in-at-the-deep-end which perfectly suits my characters' dilemmas, all are far better than I could have hoped. So while the inside of the book is currently a snakepit as far as I'm concerned, the outside of it is wonderful, and I keep grinning at my copy.

To give you a fuller virtual experience, here's the jacket blurb:

In a tense, divided court, a young princess watches her mother struggle to hold the throne. On a secluded coastal estate, a scholar finds a child washed up on the shore.

Anne. Henry. A Christian princess of the royal blood. A pagan bastard, groomed all his hidden, lonely life to make a grab for the crown.

In this work of stunning imagination, Kit Whitfield has written a fictional history at once familiar and alien. Since the ninth century, when the deepsmen invaded Venice, an uneasy alliance has held between the people of the land and the sea. That alliance was brokered by the warrior queen, Angelica, half landsman, half deepsman, the mother of the royal houses of Europe. Now, centuries later, no navy can cross the seas without allies in the ocean - and without deepsmen guarding its shores, no nation can withstand invasion. The hybrid kings keep the treaty between both sides, protecting their people from the threat of war.

The royal blood is the key to peace, and ferociously protected. The penalties for any landsman who tries to breed with a deepsman are severe; the fate of any 'bastard' child, born of such an illegitimate union, is terrible. But the royal house of England is staggering, collapsing under the weight of centuries of inbreeding.

Anne prays for guidance, a way into the future without hatred or bloodshed. Henry holds with fierce certainty that only the strong survive. But if either of them is to outlive the coming conflict, they may need more than faith alone...

Anyone want to play a game? Who can come up with a first sentence for that book? Both comedy and serious suggestions will be welcome. Accurate guesses will be met with tremendous kudos and suspicious glances. Come on, have a go...

LATER: my delightful publicist has told me that we can send a free copy of In Great Waters to the lucky winner of this first-lines competition that seems to be building up! So, let's say for the sake of convenience that the competition closes at midnight on Saturday, Greenwich Mean Time. Let's hear from you lovely people, and a shiny book could be yours.

Monday, January 05, 2009

Exorcism isn't a game

To summarise for those who aren't familiar: the film is an Americanised and sensationalised account of a real case, that of a young German woman named Annaliese Michel, who died tragically at the age of twenty-three following a set of exorcism rituals which led to the two priests who 'exorcised' her and her parents being convicted of negligent homicide. Suffering from both epilepsy and depression, Annaliese became convinced she was possessed and, being devoutly Catholic, appealed to the Church to exorcise her. Following her death, the Church changed its position and declared her to have been mentally ill rather than possessed, but two priests did attempt to exorcise her - not once, as The Exorcism of Emily Rose suggests, but sixty-seven times. Giving up medical treatment with the support of the priests, Annaliese and her family put themselves entirely in their hands; she took to refusing all food, which, along with dehydration, eventually caused her death.

The Exorcism of Emily Rose isn't the only film made about this lamentable case. There's also Requiem, a German film I'd highly recommend: a moving, intelligent and naturalistic examination of the incident that takes an entirely different line. Rather than being about the exorcisms and their aftermath, the scariness of showing the audience demonic visions, it follows the young woman (called Michaela in this version) from the time she begins to believe she may be possessed up until the time she consents to the series of exorcisms, asking the really interesting question: why would a bright, modern young woman possibly submit to such a process? The presentation is a great deal sadder than The Exorcism of Emily Rose - Michaela's personality is much more of a factor, and she's presented as an exceptionally nice girl - and the 'possessions' are filmed from the outside. We see her collapsing or finding herself unable to touch a crucifix, but with no special effects or melodramatic music whether the cause is medical or spiritual is entirely up to the viewer.

The film's interpretation tends towards a psychological explanation: Michaela, accurately, is described as having suffered a debilitating form of epilepsy that's proved resistant to treatment for some years prior to possession ever becoming a factor (The Exorcism of Emily Rose suggests that the onset of fits and demonic visions occurred simultaneously, lending support to the idea that she might not have had epilepsy at all, which is not how it was). Michaela is aware she has epilepsy and so is her family - in fact, that's part of the problem. Requiem presents a family not just devout but tired and sceptical of doctors. Medicine hasn't cured Michaela, who's been sick for years, and her family are unwilling to trust doctors again; Michaela in particular is unwilling to accept medical treatment because the amount of freedom her family allows her has always been heavily dependent on her seeming well - for her, a medical diagnosis has long been associated with a punitive consequence. Similarly, her family is rather fraught: her mother is presented as a negative and disapproving woman who constantly treats Michaela as if there was something bad about her, even though Michaela's a nice and responsible girl; accepting the exorcisms is a way of reconciling herself with this difficult parent. There's also the issue of her relationship with the priests (two of them, again accurately, rather than the single priest of The Exorcism of Emily Rose), which has another influence: one is an ordinary, elderly parish priest, sceptical of the idea but without the strength or certainty to resist the escalating events, the other a young and idealistic man driven by good but dangerous intentions - possibly a sense of chivalry towards this beautiful young woman, and certainly a sense of personal spiritual crisis. While it's not discussed in detail, he remarks, 'The world makes our souls sick. I was close to despair' in their first meeting, talking of the world's over-reliance on science and the fact that an answered prayer doesn't necessarily prove the existence of God - suggesting that his own faith is less secure than he would wish it to be. Later on he tells Michaela, 'I have to see it as a trial or there is only despair left to me,' more or less acknowledging that his own emotional needs are driving him. He insists that Michaela is being 'tested' because she's 'special', perhaps seeing what he wants to see: a real spiritual drama, far removed from his regular round of giving sermons to small congregations and being asked to bless cows - a proper professional challenge to revive his own faith.

The personalities of the five people involved, in short, mesh together: Michaela's exhaustion with her own illness and the doctors' failure to cure it, her desire to be at peace with her mother, and perhaps the sense that it's easier to slip into being a martyr than to fight both her illness and the world for independence; her father's desire to see her better; her mother's sense that there's something wrong with her; the older priest's failure of certainty; the younger priest's need for something extreme to make his priesthood seem worthwhile to him. Five basically decent people influence each other into a terrible mistake. Michaela's fits, which are not the main focus of the film, seem a combination of her epilepsy and an expression of the stress she lives under, perhaps an opportunity to act out her desperation, her submerged anger towards her family and her fear that it's all hopeless; the slide into 'possession' seems as much an emotional breakdown as a case of epilepsy.

So Requiem is a plausible account of events, but one that doesn't pretend to precise accuracy. The beginning credit reads: 'Requiem is based on real events but the characters and situations portrayed in the film are fictional.' (Or 'freely imagined', in another translation.) It's a sensitive consideration of how such a tragedy might have happened, and as such, is an admirable film.

The Exorcism of Emily Rose, on the other hand, is problematic. Set up as a courtroom drama, it begins with the girl's death and follows the trial of 'Father Moore' (not the parents; 'the priest admits he ran the show' someone explains, which apparently acquits them) for negligent homicide, interspersed with flashbacks to the 'possession' and the exorcism. On the one hand, the movie strays much further from the real events than Requiem - but on the other, it's much less clear that it's fictionalising. At times, it comes uncomfortably close to suggesting that it's preaching the truth.

To begin with, the opening credit reads: 'This film is based on a true story.' Just that. 'Based on' is a phrase open to interpretation - you can diverge a long way from a story you're based on - but without Requiem's careful acknowledgement that a film version isn't, can't be, an accurate account, there's already more of a claim to verisimilitude in the first few seconds. And it's not just in the title card that truth is vaunted. The priest on trial returns again and again to the importance of 'telling Emily Rose's story', 'what really happened and why': structurally, the movie is of course 'telling Emily Rose's story', but by bit, in the same way and in the same order that the priest wants it told - which, it's later implied, is also following Emily's dying wish of spreading the 'truth'. The set-up of the story thus carries a heavy implication that, in spreading her 'true story' to a wider audience, it's following the fictitious Emily's request.

But a lot has been changed - important things. The film makers aren't interested in the psychological dymanics that preceded the 'possession'; we hear from the mother that 'Before she went away to university, my Emily was so very happy,' and, as I've said, there's no suggestion of epilepsy before the demonic visions began. 'We never had any problems like that before,' the father declares. Emily was 'completely normal' in between demonic episodes, someone explains, which proves that she wasn't mentally ill or epileptic, presumably because ill or epileptic people never, ever have moments of clarity - which will come as something of a surprise to anyone who actually knows a person with mental illness or epilepsy, because in reality almost everyone with such a condition is lucid a fair proportion of the time. In this version of events, it's possible to conclude, as some characters do, that she never suffered from epilepsy at all; there's certainly nothing in the story to suggest that there might have been problems within the family that allowed their daughter to die.

The trial, instead, is set up as a conflict between faith and science. 'We're going after a holy man,' remarks one lawyer, and the prosecuting lawyer's belief that a priest should be held to higher standards than the average person, and thus punished more severely is dismissed by the defense lawyer as a lack of the 'forgiveness' and 'compassion' that the prosecutor's religion dictates. In fact, religion isn't given much more of a context than this. Requiem paints a detailed portrait of a Catholic life in the 1970s, but we don't see the details of Emily Rose and her family's belief in anything other than demonic possession; the priest's teachings to his lawyer consist largely in warning her against demons. The prosecutor closes his case by calling the priest's beliefs 'superstition', the defender with the statement, 'I cannot deny that it's possible', as if the issue was about the existence of demons rather than about neglect of care - care you'd expect a priest to take seriously, demons or not. The issue the film is really interested in is not 'How could this happen?', as with Requiem; it's interested in asking whether 'Emily Rose' was really possessed. And it tends towards the answer 'yes' - because, after all, that makes for a more exciting horror movie.

In an interview, the makers commented quite correctly that they had taken 'certain dramatic license', remarking thus: 'My angle is, even if I don't believe necessarily in demonic forces, I think it's cavalier to dismiss people's beliefs when they have real credibility about what they feel and what they believe.'

Just from an artistic position, I do agree that even-handedness when portraying religion can be a worthy aim; my upcoming book, In Great Waters, attempts to do just that, revolving around two central characters, one deeply religious and the other unshakeably atheist. People being what they are, I suspect that Christian readers will consider it to be proselystising atheism and atheist readers will think it's preaching Christianity, which should be fun, but I'm doubtful when it comes to The Exorcism of Emily Rose. The apparent confusion over the word 'credibility' in that sentence - someone can't have 'credibility' about what they believe; credibility is about track record and actions, not beliefs and feelings - is not, I think, just me being a grammar snob. The word seems to imply a conflation of two different things: belief and believability. Believing something deeply doesn't make it credible to anyone but you - and ascribing someone credibility purely on the basis of their strong faith is a dangerous business. You can respect someone's right to believe without having to endorse what they believe.

So trying not to dismiss deep faith out of hand is fine as long as you don't start pretending to agree just to be polite - but adding more and more to the story to weight it in favour of those beliefs is more than just showing respect. (It's worth pointing out that the makers of The Exorcism of Emily Rose had no contact with the Michel family, while the director of Requiem met one of Annaliese's younger sisters several times; interest in the real people, which is an important element of respect, is on Requiem's side.) But leaving aside issues of who consulted who, it's perfectly possible to depict people as sincere in their beliefs, entitled to their beliefs, motivated by the best of intentions - yet still misguided or irresponsible in how they carry them out. One neutrally-presented exorcism after which the daughter dies, which is not what we get, would look like an ambiguous tragedy. One wildly dramatised exorcism in which lightning flashes and snakes and cockroaches swarm from all sides, which is what The Exorcism of Emily Rose gives us, looks like Satan killed your daughter. But sixty-seven exorcism rituals in which the daughter's knees ruptured from the genuflections, which is what actually happened, looks like a reckless disregard for her safety - and to rewrite that with added creepy-crawlies isn't what the film makers call 'some kind of even-handedness', it's taking sides. We see a few moments of 'possession' revisited, staged as if they were ordinary fits, but nothing like as many, and nothing like as compelling: the drama is all on the possession side. The film makers' addition of a doctor who attended the exorcism - no doctor attended the real exorcisms, which may be one reason why Annaliese died - is whitewashing. Add to that the 'based on a true story' premise and we have a highly slanted film pretending verisimilitude.

What's particularly troubling is the change in the girl's motivation. In the movie, Emily accepts her suffering because it will prove to others that demons are genuine. 'Through you, many will come to see the realm of the spirit is real,' the Virgin Mary tells Emily in a vision, and Emily herself adds, 'Through my experience, people will know that demons are real. People say that God is dead, but how can they think that if I show them the devil?' Watching this, I felt an instant, reflexive scepticism, though it took me a moment to work out why - and later on, to discover that my instinct was correct. Annaliese Michel was Catholic, and suffering to prove the reality of your faith isn't a Catholic thing. It's an old joke that Protestants believe and Catholics know; Catholicism isn't concerned with proving its truth. That might be the motivation of an American Evangelical Protestant girl, perhaps, but not a German Catholic - and in fact, my reaction was correct: Annaliese fasted herself to death because she believed it would atone for the sins of apostate priests and sinful youth. 'Offer it up': that's a Catholic motivation; it's what the nuns told my mother to do if she complained about something. Possibly this is just cultural misunderstanding - the subtleties of a faith are not necessarily clear to someone who isn't used to it - but it also feels disturbingly like a shout-out to the audience. I suffered torments to prove demons are real, and now this film is spreading the word! You have to believe! The girl's sufferings are undoubtedly distressing, and if an audience member accepts the 'based on a true story' motif, continuing in the belief that demons aren't real feels uncomfortably close to turning one's back on a young woman in pain. It puts a certain emotional pressure on the audience to believe in demons - one that your average viewer is more than capable of resisting, no doubt, but still a rather odd change on the part of the film makers. Emily is presented, in fact, as someone we should believe in if we want to enter a richer spiritual world: 'I never knew how dead I was until I met her,' her boyfriend declares, with the strong implication that the audience are equally dead if they don't believe in her story. The closing credits conclude, 'As Emily predicted, her story has affected many people' - citing a prediction that Annaliese Michel didn't actually make, and again supporting the sense that the film is a continuation of the fictional Emily's need to get the story out to as many people as possible.

So the film makers' claims of neutrality don't hold up when you compare the film with the real case. If you change a lot of facts, and everything you add or subtract is a change that favours one side, you're being about as fair and balanced as Fox News.

Let's be fair ourselves. Based on interviews with them, I actually wouldn't assume that the film makers are trying to proselytise a belief in demons. It's easy to get swept up in a story and end on the most dramatic note, even if it doesn't express what you really think: Stephen King concluded Gerald's Game by having the heroine declare forthrightly that 'the only reason a man sticks a ring on your finger is because the law no longer allows him to put one through your nose.' If a happily married male writer can get sufficiently caught up in his story to go with the rousing conclusion that all men are domestic abusers, it's reasonable to conclude that secular film-makers can get sufficiently caught up to go with the idea that demons are real just because it makes things more exciting - especially as both King and the makers of The Exorcism of Emily Rose are working in the same genre, horror, a class of story where drama and shock are supposed to prevail over reason and balance.

If anything, I'd interpret their favouring of the possession idea as a writer's argument for freedom of the imagination - one of those little manifesto thoughts that can slip unconsciously into a narrative. 'Facts leave no room for possibilities,' declares the defence lawyer in what's almost a pre-emptive strike to anyone who points out that the film is factually inaccurate; talking to the jury, she speaks of Emily Rose's story as a chance to believe in 'a more magical world'. Writers need freedom to imagine whatever they wish, and sometimes they can get caught up in expressing that need. I would interpret the film's bias as an expression of the film makers' desire to picture and create something 'magical', rather than necessarily an attempt to convince the audience about demons: an attempt to assume an intellectual position they wouldn't ordinarily hold, in the same way a dancer might strike an unfamiliar pose to see how it felt.

But if you're selling it as a true story, and changing things to make the film evangelical in its tone if not in its intentions, you're being profoundly irresponsible. Because people believe in demons in the real world. And not just mentally ill people.

A while ago I solicted donations on this blog following a documentary called Saving Africa's Witch Children, which you can see here: parts one, two, three, four, five and six. The documentary is extremely upsetting, be warned; if it's any consolation, it would appear that following the documentary, steps are being taken to arrest the murderers and stamp out the practice, which is a fine thing. The situation is this: in Nigeria, a moral panic has built up around the idea that witch children are causing havoc in their villages. A child so accused, who can be a mere baby, is liable to be ostracised, starved, beaten, burned, cut, tortured and either murdered outright or 'exorcised' to death.

Now, according to the documentary, there was a terrible upswing in such cases following the widespread release of various movies describing how 'witch' children can wreak evil, particularly a film called End of the Wicked, produced by Liberty Films, a branch of Liberty Foundation Gospel Ministries. The documentary quotes the minstry founder Helen Ukpabio's website, which boasts that 'Liberty Films delivers the truth in a fresh and exciting way, and has led to the deliverance and salvation of many. Our books and publications also enhance the message of deliverance and hope to all those in the clutches of Satan.' The documentary makers went to interview Helen Ukpabio herself, a quick-tempered woman with a lot of blood on her hands whose main response to the suggestion that innocent children were being murdered by people who believed in her message was to turn on the interviewer (a white woman) and accuse her of racism - demanding, among other things, why she wasn't also challenging a white woman like J.K. Rowling ('Do you go to ask her? Is it because it is Africa?'), a challenge so ridiculous in so many ways that I'm not even going to bother deconstructing it. (If you don't have time to watch the whole documentary, you can see the interview at the beginning of part 5.)

In the light of this, a fairly throwaway line in The Exorcism of Emily Rose assumes a rather horrifying undertone: an academic expert witness is called to defend possession, being a specialist in 'contemporary cases of possession, mostly in the Third World.' Like, perhaps, Nigeria, where they pour acid on five-year-olds? It's at this point that the film's quest to prove 'a more magical world' starts to seem really questionable. This expert witness is described as one who studies possession 'from a scientific perspective and doesn't try to debunk it' - which seems an odd understanding of what 'scientific' means, given that the whole scientific method depends on trying to disprove things and considering theories valid only if they can withstand people 'trying to debunk' them with great energy: the implication, bizarrely, is that scepticism is unscientific. But it goes beyond that. One man dismisses the idea of citing such possessions on the grounds that the Third World is 'primitive and superstitious', which neatly implies that it's only racism and cultural prejudice that would make you doubt such beliefs - rather similar to the line Helen Ukpabio takes, in fact - but I would argue that actually, by making a vague gesture at 'the Third World' to back up the fictional story is rather closer to the cultural prejudice Chinua Achebe describes as 'reducing Africa to the role of props', 'Africa as setting and backdrop which eliminates the African as human factor.' People die of exorcisms in Africa as well as in the West, and they all matter equally; casually nodding at 'the Third World' shows a certain disrespect for the fact that ideas about possession are a real problem for real people there, not just a generic cultural background.

The situation in Nigeria only one example, though a particularly recent and heartbreaking one; people's courses of action are often influenced by fictional representations of real, or purportedly real, phenomena. The psychologists who tried to treat Genie, a girl rescued from a home so abusive that she had been denied any kind of conversation and had a vocabulary of about two words ('stopit' and 'nomore'), watched Francois Truffaut's L'Enfant Sauvage, an account of the similarly languageless Victor 'the Wild Boy of Aveyron' for inspiration.* That's a mostly benign example, though Michael Newton points out that it may have been problematic - 'More negatively, the misleadingly upbeat ending of Truffaut's film (in which Victor appears to be heading for a full place in the human community) may also have subtly influenced the scientists' expectations about the possible outcome of their work ... More than this, Victor's story might have helped to create for the Genie team a narrative in which the role of heroic educator was uncast. Perhaps it was now the subtle and in many ways understandable conflicts began in which each sought to assume the part of Genie's saviour.' (Conflict between her potential parent figures led to her life being disrupted in various damaging ways.) And the scientists themselves acknowledged potential issues: 'All of us saw in the movie what we were prepared to see to confirm our own biases,' remarked one of them. ** Intentions were honourable, but Genie's life went downhill nonetheless, and while it would be silly to blame Truffaut for this, his influence is acknowledged to have at least been felt in the tragedy.

There are more dangerous examples. A lot of the thinking behind the 'Satanic Panic' of the 1980s, in which daycare attendants were accused of grotesque and implausible abuses, traces back to the book Michelle Remembers, a supposed personal account of ritual abuse based on the 'recovered memories' of a woman known as Michelle Smith - 'memories' that there's a lot of evidence against, such as yearbook photographs of her taken at a time when she claimed to have been locked in a basement round the clock, and that are most probably the result of false memory syndrome induced by her psychiatrist, who co-wrote the book.*** A lot of people went to prison over those years.

It's worth noting that, leaving aside the Genie example on the grounds that it was a secular attempt to help someone rather than a moral panic, these things crop up in different continents, and they bear a fair resemblance to each other, people being people wherever you go. Daniel Radosh's Rapture Ready!, for instance, refers to an American kids' show called Bibleman (a superhero for the Lord) where one villain zaps children with something called a neuroiconoclasticskepticizer, 'which causes them to go glassy-eyed and say horrible things like "I don't wanna go to Vacation Bible School." Because there's no way a child would say that unless he was under some evil influence.' Similarly, also cited by Radosh, the novels of Frank Peretti discuss people being latched on to by demons who infect them with lust, or greed, or whatever. Of course, that's fiction taking some artistic license - Peretti, according to Radosh, 'stresses that he doesn't have any theological expertise, much less personal experience of demons; that all he does is take concepts he finds in the Bible and invent fantasies about them. And yet many people refuse to believe him. Terri was one of them. "With how vivid he puts everything, I honestly think that's something he doesn't just come up with. I think it's got to be something he experiences and walks in. I do feel like he's experienced those things."' And, again, of course, the idea that people can't possibly just be inventing stuff is by no means confined to the religious - but there is, at least, a theological consistency between these American tales and the African ones. In End of the Wicked, the child heading the coven tells a member, 'I invoke upon you the spirit of stubbornness ... lack of interest in school, waywardness, unsteadiness, bad company...', which sounds pretty neuroiconoclasticscepticizing. The idea that ordinary annoying qualities or vices are imposed from without by bad spirits is not confined to one culture. Of course, these American examples are just pop culture and nothing like as gruesome in their consequences as Ukpabio's film - but possession is a real idea in the West as well as elsewhere. Consider 'exorcism therapy' - there's an abstract for a study of it here, which comments 'Although many patients subjectively experienced the rituals as positive, outcome in psychiatric symptomatology was not improved. Negative outcome, such as psychotic decompensation, is associated with the exclusion of medical treatment and coercive forms of exorcism.' - and those two examples took me about ten seconds to pull of the Net. Now imagine your community pressing you to accept exorcism rather than medication while your brain was slowly crumbling from within. Which is why it's serious no matter what the country if people start believing that physical abuse or neglect, and withdrawal of medical help, is the answer to 'demons'. Exorcism and possession may sound weird to many of us, but they aren't quaint or obscure. They're real beliefs having a real effect on real people suffering from real illnesses - and it's happening today.

Here's an article in the Guardian about the phenomenon, described as 'a form of spiritual abuse' by a reverend - who points out that 'sexual abuse, homosexuality and unwanted pregnancy were often seen as routes for demonic possession.' The idea that religion might step in declaring 'More needs she the divine than the physician' is not confined to fiction: it's happening in the world around us. Even if people don't die in the exorcisms - and of course, most don't; Annaliese's case became famous because it was extreme, not because it was unique - they're still at risk. One of my friends who's suffered from mental illness made the following important point: while it's not uncommon to personify your illness to some extent - I Don't Want To Talk About It by Terence Real gives examples of men identifying their depression as a gorilla, a shark or Hitler; Churchill famously called his 'the Black Dog', Antonia White referred to hers as 'the Beast' and so on - there's a real danger in personifying it and then putting control of it in somebody else's hands. If you decide your illness is a demon and then try to cope with it yourself - ignoring thoughts that seem characteristic of the illness because that's the 'demon' talking, trying to build on the positives in your life to reduce the 'demon's' influence over you and so on - then you're really not doing much more than a religiously-toned version of CBT. But if you put yourself in the hands of an exorcist, you're setting up a situation where you can't control the illness/demon, where it has to be removed by an external force. It's an extremely good way to reinforce a sense of helplessness - and the thing is, controlling a mental illness has to be done by the patient. Nothing else works. The patient may use resources to fight the good fight - medication, CBT, therapy, exercise - but they're only effective if they patient is deliberated and self-determinedly using them as weapons against the disease. A priest who says, 'Your illness is a demon trying to distract you from God; you can overcome it if you try' may be being unscientific - and irresponsible if they also discourage their parishioner from taking necessary medication - but they are at least granting the parishioner some of the autonomy and dignity that are so vital if someone is to fight the sickness. A priest who insists 'You're possessed by devils, and you must put yourself in my hands' isn't just blocking a medical path, they're convincing their parishioner to believe themselves unable to control their own disease. They've usurped the role of General that should be occupied by the patient and demoted them into disputed territory - and territory can't fight for itself. It's one of the world's nastiest self-fulfilling prophecies.

And the numbers are surprising. According to the Washington Post, 'Exorcism is far more widespread today than most people imagine. According to Richter, there are about 70 practicing exorcists in France and just as many employed in Italy. In July this year, a congress in Poland was reportedly attended by about 350 practicing exorcists.' It's a minority activity, but it's not a one-off. It's seriously practised.

Prayer and medicine together are fine, but mental illness is a horrible scourge that desperately needs proper treatment. Considering the case of Annaliese Michel, I'll have to acknowledge my own limited expertise: she suffered from epilepsy and depression, and possibly more besides. I'm not a psychiatrist. I know one person with petit mal, which is nothing like as drastic as Annaliese's condition - but which definitely needed medication: epilepsy creates electrical storms in the brain which can cause permanent damage there, and it's crucial to keep fits to a minimum; encouraging someone with epilepsy to do otherwise is encouraging them to court injury. I know a lot of people with depression, though. The frightening thing is, it can look a bit like demonic possession; I've said elsewhere that when dealing with fiction, at least, the idea of depression as a possessing force - 'parasite personality' is the phrase I used - is grimly convincing. I've seen people I love lose it when their depression overwhelmed them, and it's a scary thing to watch. Body language changes. The face contorts into a different and worrying expression. The voice changes tone. Empathy breaks, emotion overwhelms the sufferer and isolates them from their normal selves and from those around them, leaving an observer to feel as if there are two different realities in the room, one normal and one malign. At its most severe, depression is a very frightening sight, and considering it a possessing force, metaphorically at least, is not as wild an idea as it might sound if you haven't seen it. And that's just depression on its own, never mind depression combined with epilepsy and who knows what else.

So if I had a child who was this sick and acting this alarmingly, and if I was deeply religious and believed in demons, and if medication wasn't working - because while it usually helps, it can take time to act, it can take time to find the right prescription, and some diseases are distressingly resistant to treatment - what would I think? Wouldn't I want my lovely child back? Wouldn't I be frightened of the thing that was destroying them? And if I was encouraged to think so, mightn't I be inclined to believe that it was the devil's work? I'm an agnostic and sceptical about any tales of the devil, but after seeing mental illness I have a vivid mental image of him nonetheless: having known mental illness, I feel like I've met the devil. And I'm secular. How hard would it be for someone who did believe in the devil not to feel his presence if your child seemed to be losing herself?

And if I was a member of a faith that believed in demons theoretically, but had never expected to meet one myself - and my child started acting desperately sick - and I'd seen a film I believed to be based on a true story that supported the idea of exorcism - mightn't I factor that film into my thinking when deciding what to do? I don't believe any one film ever converted anyone to a course of action - End of the Wicked would have done little harm in Nigeria if people there weren't ready to believe in spirits and demons to begin with - but there's such a thing as a push in the wrong direction. Nigeria had a combination of traditional beliefs and Pentecostal Christianity that laid the groundwork for 'witch children', and the West has a combination of Christianity and hostility to psychiatry that lays plenty of groundwork for negligent exorcisms.

Because it's not just cases of terrifying acting-out that are a cause for concern here. Mental illness is plenty stigmatised as it is, even in its less extreme forms. The world is full of people eager for some other explanation, any other explanation, than 'mind diseased'. One of the many lousy things about mental illness is that from the outside it looks, well, completely irrational. There's nothing physically wrong with the patient - or at least, nothing you can detect. (Actually there probably is something physically wrong in their brain tissue; recent findings suggest that depression is neurodegenerative, for instance, but the lesions of a mental illness are tiny and delicate, and hidden inside a skull, so the naked eye can't pick them up.) As a result, there's always a massive temptation to assume that the patient has nothing really wrong with them except their behaviour, that if they just pulled themselves together, or prayed themselves clean, they'd be fine. There's a lot of hostility to medication when it comes to mental illness; people love to talk about us being an 'overmedicated society', even when many mentally ill people actually don't get the treatment they need. Yes, doubtless some doctors overprescribe things like Prozac - you can find doctors who overprescribe most things. But mental illness is extremely common; a doctor friend of mine estimates that three out of four people will suffer at least one depressive episode in their lives - so even if the majority of people were being prescribed a drug for mental illness, it would actually be a case of sick people getting what they need rather than a sign of a degenerating culture - and sick people getting treatment is a sign of a culture being healthy and well-run, not of degeneration. It's when sick people aren't being treated that a culture's in trouble.

This 'overmedication' scare doesn't attach to non-psychiatric medication. Close to a hundred per cent of people in the West have taken aspirin at some point in their lives, but I don't hear much outcry about us being an overmedicated society because of that; it's assumed that people take it when they need it. It's generally agreed that antibiotics, which most people have taken at some point, genuinely are overprescribed, with measurable bad consequences for humanity (I've never heard of SSRIs creating a 'superdepression' or anticonvulsants creating a 'superepilepsy'), but people are nothing like as eager to point to antibiotics as the sign of decadence. It's agreed that they're very valuable when prescribed correctly, misused when prescribed unnecessarily, and should therefore be used appropriately. Tell someone you think you need antibiotics for your sore throat, and they're most likely to suggest that you consult a doctor to see if you're right - but try telling someone you think you need antidepressants, and watch how uncomfortable they get ... and how likely to suggest that you try other alternatives first. Taking antibiotics for a chest infection is considered an appropriate use of medication, but for far too many people, antidepressants are considered a lack of spine and independence, a flabby failure of will, a desire to medicate yourself out of normal emotions you're too weak to deal with. (Rather than what they are, which is a treatment for organic brain dysfunction in which abnormal emotional pain is one of many symptoms.) In situations like this, a religious person is all the more likely to reach for prayer as a first resort: after all, God is supposed to deal with matters of the spirit. (Plus, of course, medication can take a while to work, and we want instant results. Not even because we're an 'instant gratification culture', but because if you or a someone you love is in pain, you want that pain stopped as fast as possible. The Exorcism of Emily Rose blames 'Gambutrol' - a fictitious anticonvulsant - for failing to cure Emily's fits immediately, but plenty of drugs take a while to have an effect. Patients prescribed SSRIs are generally warned that their symptoms will actually get worse before they get better.) To suggest that it's all right to support a mentally ill girl in her refusal of medication is tantamount to suggesting it's all right to encourage a cancer patient to reject surgery because they believe a trip to Lourdes will fix them right up - only more so, because we live in a society that puts up a lot of resistance to medical care for the mentally ill as it is, whether religious or secular. You don't have to be religious to feel that not taking medication that would very likely cure a terrible disease has a certain moral cachet to it. The Guardian article I cited earlier quotes the Mental Health Foundation: 'The charity warned that the notion of demonic possession could be extremely damaging when linked to people with a label of mental illness and "risked conflating notions of evil and ill health."' In a culture where even secular people are unwilling to accept the idea that mental illness isn't somehow the patient's fault, such notions can be incredibly dangerous.

Mental illness rips people up in every country in the world. In many of those countries, there's resistance to getting it properly treated - even in technologically developed countries where decent treatment is available. The anger I feel at the harm such illnesses cause people is hard to express without sounding unstable myself, so I'll confine myself to saying that one reason why I'll accept a personified version of someone's illness in real life is that it allows me to fantasise about finding that personification and torturing it to death. But I know, more than that, that it's never okay to torture the person in the name of getting at the disease.

The thing is, when making a horror movie, mental illness is a rather convenient toy to play with. 'I'm not crazy!', character after character cries; the monster's real, and the psychiatrist who tries to treat them is an obstacle to solving the problem, an ignorant know-it-all trying to force someone to give up their truth. It's an issue such stories have to address, because someone insisting the boogyman is after them probably would run into questions about their mental health pretty fast, but that doesn't make it okay to be cavalier. Like Africa, mental illness shouldn't be treated as a prop.

Dealing with serious matters like this, the artistic duty of honesty becomes more sacred than ever. It's always important to be truthful, whether you're producing the next arthouse masterpiece or a mass-market popcorn fest: art expresses, and has to reach for something worth expressing. Simplifying a story to make it fit into a two-hour film is fine; the amalgamation of the two priests who exorcised Annaliese Michel into one priest who exorcises Emily Rose, for example, is fair enough. Unless the relationship between the two priests was a crucial factor, it doesn't change the essentials of the story. (Though Requiem kept the two priests, of course, and it's still a better film.) The story of Annaliese Michel is a complicated one: unlike the young victims in Nigeria, she actively participated in the belief that she was possessed, so the withdrawal of medical treatment and exorcisms were done with her consent. In such cases, new questions arise: if someone's not in sound mind, at what point can their consent be trusted or overridden? These questions are serious because they stray, even without religion, into dangerous territory where the dignity and autonomy of the patient can be violated, where their rights and their best interests may seem to conflict, and there are no easy answers. In such situations, in fact, easy answers must be resisted, because they'll probably end up damaging the patient. The case of Annaliese Michel seems largely like a failure of pastoral care on the part of the Church; an ordinary family can't be expected to be experts either on psychiatry or on theology, and it should have been the duty of the priests to ensure that she got proper medical treatment as well as prayers, even just on a common sense, belt and braces principle. They succumbed instead to a common failing: viewing medicine not as an ally but as a competitor - to the point where it doesn't seem to have occurred to them to do what The Exorcism of Emily Rose pretends they did, and brought in a doctor to make sure she wasn't injured in the exorcism process. Such a situation involves a complex diffusion of blame, and anyone trying to depict it owes it a lot of care and thought.

As it stands, though, The Exorcism of Emily Rose seems to have struck truth a double whammy. On the one hand, the laudable aim of being understanding towards those whose beliefs or actions are abhorrent to you - a fine thing for art to do - has overshot: so much time and emotional energy is spent presenting their perspective that the alternative, you-shouldn't-let-people-die perspective fades into the background. On the other hand, the film makers have gone for sensational scenes with bugs and thunder galore, plus creepy manifestations affecting other characters to add to the spookiness, which in terms of spectacle and the evidence of our own eyes seems to provide tremendous evidence for the idea that there really were demons in the girl. Broad-mindedness and a desire to be spectacular have forged a strange alliance.

If it didn't make an issue of being based on a true story, and lay so much emphasis on the 'true' girl's desire to have her story told, this wouldn't be so much of a problem. But as it is, the result is a film that comes uncomfortably close to suggesting that letting a sick girl starve to death is really not a big deal, morally speaking, just as long as you're convinced you're acting for God - which, according to the film's visuals and the characters we get to hear from properly, you actually are.

Morality, as a result, winds up oddly constrained. We never hear very much from the Christian prosecuting attorney, for example, who believes in God but believes the priest sinned nonetheless. Such a position, which you'd think would be a perfectly sound one, is treated only as an antagonist's stance, there to be defeated. Not only do we see compelling portraits of Emily's visions, but the supernatural effects bleed out into the rest of the story: as early as fifteen minutes in, our lawyer heroine finds her watch stopping at 3am, the witching hour, and she too is plagued by night terrors. She finds a gold locket with her initials on the street, and takes it as a sign from God, wearing it on the priest's advice. This looks more like stealing than faith - you'd think she should have at least tried to find out if the valuable trinket had a rightful owner, not to mention the fact that it's rather materialistic of faith to provide her with such a flattering accessory - but the film does have some moral stumbles like this. Oddly, for instance, the priest decides at the end not to go back to his parish, because he's 'seen the darkness' and feels affected by it - apparently uninterested in sharing his experiences with the souls he's supposed to be saving from said darkness. You'd think that if demons were real, people might need to hear about it, but Father Moore seems more inclined to retreat into splendid isolation than to carry on the good fight. Similarly, the lawyer turns down a partnership at her firm at the end, having previously been threatened with the sack for pursuing the trial as she thought right, apparently uninterested in the greater freedom to follow her conscience that this professional security would provide. The film makers' love of gestures sometimes overrides the sense that characters might have responsibilities that extend beyond the moment of the gesture itself, which is at the root of what's really wrong with the film.

In short, there are a lot of problems with The Exorcism of Emily Rose. It purports to be a true story while slanting both the facts and the language to favour an interpretation that justifies allowing the death of a sick young woman. Other continents and dangerous illnesses are treated as mere props to a fairly splashy horror story, and grand gestures carry more weight than serious assumption of duties and responsibilities. Its flaws wouldn't be very serious if it didn't purport to be a true story. Some horror films are inspired by real events, but if they don't claim to be actual depictions of them, it hardly matters; nobody thinks Psycho or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are accurate portraits of Ed Gein. If The Exorcism of Emily Rose had contented itself with being one of those, it would just be a descendant of The Exorcist with a courtroom twist - but the fact that it lays emphasis on telling a 'true' story invites, demands, that the audience consider it in the light of reality. And in the light of reality, it's misleading in a worrying way.

I'm not saying that people will undoubtedly start starving their children to death because of this movie; that would be a wild prediction that I have no evidence to back up, probably alarmist and certainly nothing more than ill-informed speculation about the actions of people I've never met. My aim is to talk about the film and the decisions of its makers, not to forecast the reactions of its audience. What I am saying is this: there is a history of people taking works of fiction that purport to be true - End of the Wicked, Michelle Remembers - and letting the new 'information' have a profound effect on how they behave towards their fellow human beings. Fiction does influence how we think; my impressions of Ayn Rand and Queen Elizabeth are heavily bound up with Helen Mirren nowadays, for instance, because things that strike our emotions tend to stay in our memories more than things that only touch our reason. When handling an real event - and setting out to present it as dramatically as possible - an artist ought to be very, very careful in how they portray dangerous subjects like mental illness and exorcism. People die of them. We should always try to be honest, particularly when we're creating art, and claiming greater accuracy than we should is always a questionable business. When it comes to claiming accuracy about real events that involve real dangers, that honesty becomes crucial. I'm not saying that The Exorcism of Emily Rose will influence people to start 'exorcising' people they should treat; I'm saying that if there's a chance that it might, the makers ought to have been very careful with their claims of honesty - and I don't think they were. It seems more like they tried to have it both ways: the authority of a 'true story' with the freedom to invent of a fictional one. I can't predict the consequences, but I do believe this carelessness is irresponsible.

In conclusion, I'd like to address the point that supporting exorcism is not a question of faith versus unbelief. To say that exorcisms are an irresponsible way of dealing with physical illnesses is not to attack the idea of faith. One doesn't have to support abuse to support respect for religion - and for the Christians in the audience, there's Scriptural precedent for this. I'd refer to Matthew 7 23-24: 'Many will say to Me in that Day, "Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in Thy name, and in Thy name have cast out devils, and in Thy name done many wonderful works?" And then will I profess unto them, "I never knew you: depart from Me, ye that work iniquity."'

*See Savage Boys and Wild Girls: a history of feral children by Michael Newton.

** See Genie: a scientific tragedy by Russ Rymer.

*** See Satan's Silence: ritual abuse and the making of a modern American witch hunt by Debbie Nathan and Michael Snedeker.

Archives

July 2006 August 2006 September 2006 October 2006 November 2006 December 2006 January 2007 February 2007 March 2007 April 2007 May 2007 June 2007 July 2007 August 2007 September 2007 October 2007 November 2007 December 2007 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 April 2008 May 2008 June 2008 July 2008 August 2008 September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 December 2008 January 2009 February 2009 March 2009 April 2009 May 2009 June 2009 July 2009 August 2009 September 2009 October 2009 November 2009 December 2009 January 2010 February 2010 March 2010 April 2010 May 2010